The London in whose bosom William Shakespeare lived and worked was a much smaller city than that we know today. Had a miracle transported the spirit of Geoffrey Chaucer forward two hundred years, he would have felt quite at home in the Tudor city, most of which was still confined within the walls that had marked its boundaries since it was the centre of Roman rule in Britain. Its street names were still those that had been bestowed on them in medieval times, often reflecting the trades that had long been carried on in them – think Bread Street, Butcher Row, Ironmonger Lane, and Silver Street – the main market was still called Cheapside (a cheap, or chepe, being an old word for a market), and many of the main landmarks would have been unchanged from those his pilgrims might have visited.

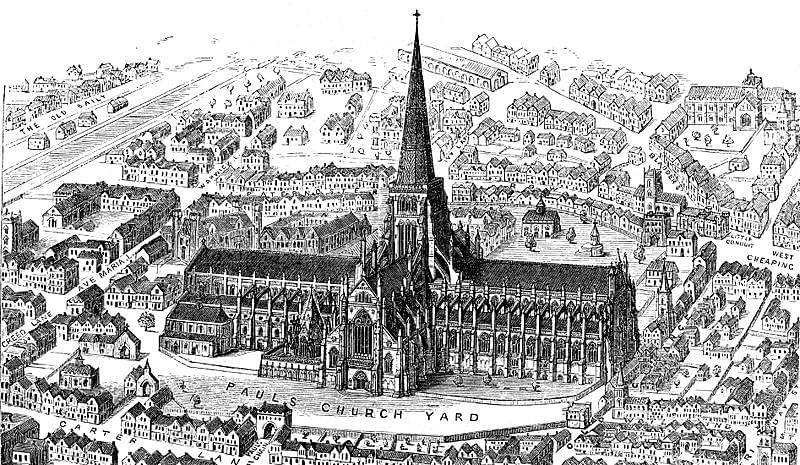

One landmark that might have puzzled him a little was St Paul’s Cathedral, the massive church that stood at the western end of the city on the slight eminence of Ludgate Hill. The cathedral was still there, but the lofty and graceful spire that had once crowned its bell tower had disappeared, destroyed in a catastrophic fire in 1561; when Shakespeare arrived in London sometime in the 1580’s, the stump of the tower was a popular place to climb and get a unique view of the city, for which the visitor paid the princely sum of one penny. Some things don’t change.

If St Paul’s was the city’s western anchor, its eastern end was moored against the grim and forbidding walls of the Tower of London. William the Conqueror’s simple keep had, by the late sixteenth century, grown into an extensive and formidable fortress, protecting the city from potential raiders coming up the Thames. It also served as both a royal palace and a prison for those of high rank who had offended the apparatus of the state – and who, if they were unlucky and unable to secure their release, might well meet their end on the executioner’s block in Tower Green.

Between these two landmarks, the city enclosed by the walls covered some 330 acres or barely half a square mile. That meant that it was eminently walkable: you could easily go on foot from one end to the other in half an hour, and that was how most people got around. Rich folk, of course, had their carriages and their horses, and no doubt were quietly cursed by Londoners as they were forced aside. And then there were drays and carts carrying produce and goods to and from the markets, not to mention flocks of sheep and other kinds of livestock being led to their fate. So walking around in the city would have involved a lot of dodging and weaving in crowded streets and shadowy lanes.

Over the century, the city’s population quadrupled from 50,000 inhabitants to more than 200,000. The city was extremely crowded as a result, and it had burst from its ancient medieval boundaries into the fields beyond. Suburbs sprang up to the north and west, while across the river the stews of Southbank had developed. It was linked to the city proper by the marvel of London Bridge, whose medieval structure was now completely covered by shops, residences and businesses rising three and even four stories above the bridge itself and teetering precariously over the rushing waters of the Thames. Because the authority of the mayor of the City of London ended at the city’s walls, these new suburbs were often wild and lawless places; Southwark in particular was notorious as the home of gaming houses, brothels, bear- and bull-baiting rings – and the theatre!

The Thames was the source of the city’s wealth, and at the same time its main highway. The warehouses that lined the northern bank received and dispatched goods to and from the world, carried in the ships that found their way up the broad, muddy waters of the river to moor at the jetties. Creaking cranes worked ceaselessly to the sound of voices and accents from every part of the world bandying insults and jokes with the stevedores, and seagulls wheeled and screeched and dove whenever their gimlet eyes spotted a gobbet of food. On the river itself, myriads of small boats could be seen ferrying passengers up and down or across, while the rich and powerful had themselves rowed in splendid barges to their destination – much quicker and more comfortable than negotiating choked city streets and muddy country roads.

No doubt, when he first arrived, Shakespeare would have found it all rather a shock after the relative calm of life in a market town like Stratford. The crowded streets rang with the shouts of vendors flogging their wares at the tops of their voices, thieves and pickpockets darted in and out deftly separating purses from their owners, dogs quarreled over scraps in the gutters, housewives shouted gossip across the gap between the upper stories of their houses as they hung washing out to dry, furious puritan preachers declaimed about the evils of the world on streetcorners, and beggars stretched their arms out in supplication. Peaceful it certainly wasn’t.

London was also a dangerous place. There were no police to speak of, just the rather inadequate town watch who policed the curfew imposed every night from sunset, after which everyone was supposed to get off the streets. It was a rule often breached, because the watch were too few to ensure compliance. If you did have the misfortune to be caught by them, you could usually buy your way out of trouble with a bribe – or, if you had a silver tongue, talk your way to safety, as the famous comic actor Richard Tarleton often did. Mind you, with no streetlights to speak of, the wise man made sure he was indoors after dark, for at night London became the realm of petty criminals who disdained to use the genteel arts of the pickpocket in favour of more direct and violent methods of extracting their living.

Life generally was a precarious business. You had to make your living however you could, working long hours for meagre pay, often in squalid conditions. If you lost your job or your business failed, there was no safety net, no social services, and you could easily find yourself homeless and destitute, reduced to begging on the streets. Often the cause of your downfall might be quite unjust – a nobleman might refuse to pay you for your services, or you might be dismissed for looking sideways at your master, or for some other trivial misdemeanour. There was usually no recourse in such cases, and if you were poor the system was pretty well stacked against you.

Even if you succeeded in making a living, other threats were ever-present. The chief of these was disease. An overcrowded, poorly ventilated and poorly sanitised city, London was prone to outbreaks of all kinds of illness. Malaria was exceedingly common, as was typhoid. And then there was the plague, the scourge that had arrived in 1348 and never left. There was no known cure, and when it struck the only thing the authorities could do was impose a particularly brutal form of quarantine, locking whole families inside their houses and leaving them until they all either died or, in a very few cases, emerged having survived the illness. If you could, you got out of the city (easier for the wealthy to do, of course) and waited it out in the country.

Yet, amid all the turbulence London was also at the centre of an extraordinary intellectual ferment. The Renaissance, having exploded in Italy in the fifteenth century, by the sixteenth had made its way to England by way of the humanists of northern Europe. Henry VIII, in between marrying and murdering wives and undertaking a religious reformation, had also been an enthusiastic patron of the arts. Painting, music and literature all thrived under his rule, and his daughter carried on the tradition, seeing herself very much as a Renaissance Princess. And it was in the development of the English language itself that the English version of the Renaissance found its greatest voice.

Though it had not been invented in England, the English took to the printing press with gusto. In this metropolitan city, ideas as well as goods flowed in, expressed and expanded in thousands of books, pamphlets and tracts published every year by the printers on Paternoster Row, just north of St. Paul’s. The cathedral churchyard itself became the focus for the book trade, and every day it was filled with booksellers’ stalls where you could buy books and pamphlets on just about any subject you could think of. It is easy to imagine Shakespeare spending all his leisure hours here, reading the works of English poets like Thomas Watson, Robert Greene, and Philip Sydney, soaking up descriptions of the New World brought back by intrepid explorers, or learning of the travels on the continent by early tourists such as Fynes Morrison.

Mind you, it wasn’t always safe to be an intellectual in Tudor England, which was by our standards a fairly formidable police state. The royal government imposed strict censorship, and employed a small army of informers to police it. Penalties for expressing views or opinions on subjects of which the government disapproved could be severe, even lethal. Any discussion of the succession, for example, was considered to be treason, particularly as Queen Elizabeth aged and the prospect of her death became more real. Political dissent was stamped on ruthlessly, and the government would employ all sorts of tricks to suppress those views that it did not want heard. If you were going to talk about a subject that was taboo, you had to do so in a careful, indirect way, something at which Shakespeare became very adept.

The most difficult subject of all was religion. After all, King Henry’s split from the Church of Rome had only happened fifty years ago, and in the decade after the old king’s death England had oscillated wildly between pursuing the path of his reformation and rejoining the Catholic world. Many parts of the country had never given up on the old religion, particularly in the north, while London was increasingly in the grip of the Puritan movement, who wanted to reformation of the church to go further and rid it entirely of what they considered ‘popish’ influences. There was much they disapproved of in Elizabethan society, which they saw as being too permissive and tolerant of idle activities that drew men and women away from the worship of God. One of the worst offenders was the theatre.

But their authority was limited, bounded by the city walls, and there was only so far they could go, particularly since the queen herself was fond of watching plays, as was most of the Tudor establishment. And hard-headed politicians like Sir Francis Walsingham and Lord Burghley saw the theatre as both an outlet for the inevitable tensions of a big city and as an opportunity to disseminate propaganda. So, in this uneasy and tense environment, theatre companies were allowed to thrive.

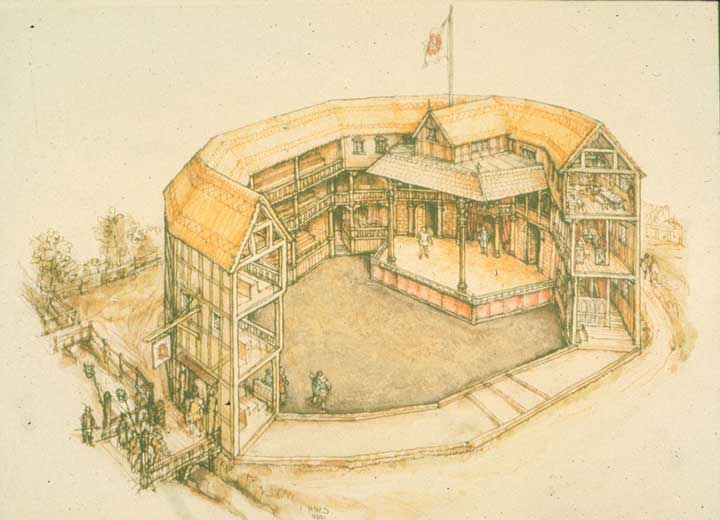

Shakespeare very likely would have seen plays enacted in the yards of the bigger inns in the city. Very few of these survive, but in his time a typical coaching inn would have had a large internal courtyard surrounded by galleried walks that gave access to the upper rooms. With the addition of a temporary stage, they were perfectly adapted to perform plays. The muddy floor of the yard was where the ‘groundlings’ stood to watch, while the gentry peered down from the galleries, for which privilege they paid an extra penny apiece.

However, most of the inns were within the city boundaries, so whenever they saw an opportunity, the Puritan councillors moved to ban the performance of plays within the walls. The solution was to go out to the newer suburbs, where they could play at inns or, even better, at purpose-built open air theatres. The first of these was simply named The Theatre, and was built in the northern suburb of Shoreditch by carpenter-cum-theatrical entrepreneur James Burbage in 1576. The Curtain followed soon after, in 1577, and for a long time these two theatres were the main locus of theatrical activity in the city, until Philip Henslowe built the Rose, over on the other side of the Thames in Southwark, in 1587.

So here, safely beyond the reach of the Puritans of the city council, Shakespeare, Marlowe, Greene, and all the other playwrights of the era could see their words transformed onto the stage for the amusement and entertainment of London’s rich and poor alike. The new theatres proved immensely popular, and crowds could soon be seen streaming north from the Bishop’s Gate heading for an afternoon’s entertainment, while over on the other side of the city patrons might go from a morning watching a bear being taunted by packs of dogs in the Paris Gardens to a performance of Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great at the new Rose Theatre in the afternoon.

This, then, was Shakespeare’s London, a city of wild, noisy contradictions. An intoxicating and sometimes frightening place, yet one full of possibilities. At times it must have felt as though it was a universe in itself, even if it was not quite yet what it became, the centre of a vast empire. It is hardly surprising that a talented young man from the provinces, sure of his own ability, found it the perfect place to realise his ambitions. For it was a place where you either failed ignominiously, or succeeded gloriously. There was no middle ground.

Anthony R Wildman is the author of What News on the Rialto? The Queen’s Player and In the Company of Knaves, a series of novels about William Shakespeare’s early life. Find out more about his books here, or click on the book cover image to view on Amazon.