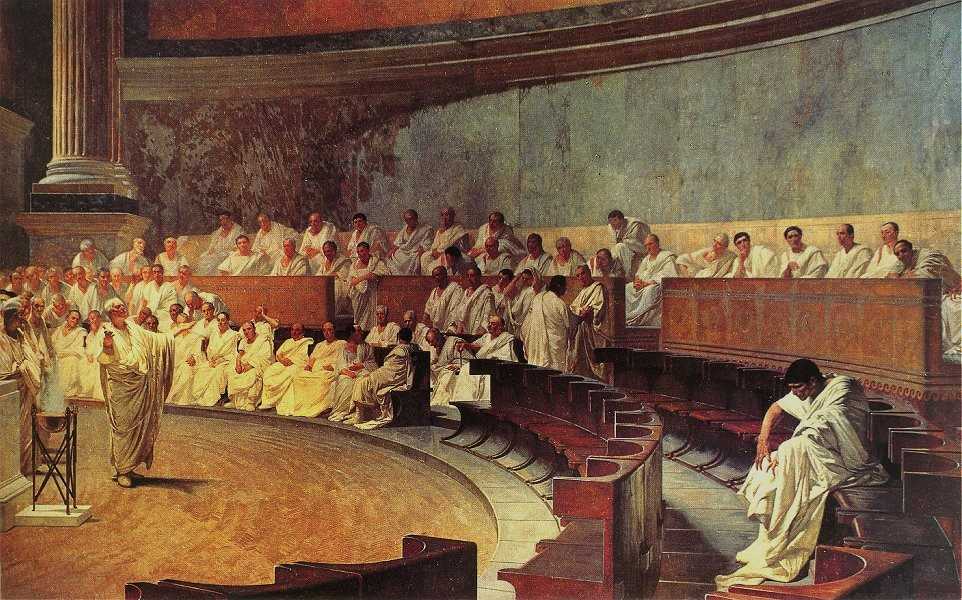

I remember seeing this picture long ago when I was a schoolboy, in some book or another, and it immediately captivated me. The scene is the Senate chamber in ancient Rome. A single figure sitting in the foreground has been shunned by the other senators and listens with his face downcast, avoiding the accusing eyes of his colleagues and no doubt trying to disguise his emotions. His accuser is a grey-haired orator who stands in the well of the Senate, arms outstretched in a classic rhetorical pose. Clearly, something historic and momentous is happening.

So who is the man being so roundly denounced? And who is his prosecutor? The title of the painting gives it away: Marcus Tullius Cicero, one of the greatest orators in Roman history, is denouncing Lucius Sergius Catilina (often anglicised to Catiline), a fellow senator and the leader of a conspiracy to overthrow the government.

Cicero, born in 106 BCE at Arpinum (modern Arpino, in central Italy), is one of the towering figures of antiquity. Trained as a lawyer, he was also a philosopher, writer, scholar and orator. He wrote a dozen or more books on philosophy and rhetoric, and was a successful and active politician during a particularly turbulent time in the history of Rome. Coming from a wealthy family of the equestrian class (the second rank of citizens in the strict Roman social hierarchy; we would probably consider him to be upper middle class), he proceeded down the typical path expected of well-born Romans, serving as a tribune under the dictator Sulla, and then entering the courts as an advocate. There, he soon made a name for himself as a skilled orator; in 76 BCE, he was elected as a quaestor (a kind of financial official) in the province of Sicily.

Returning to Rome, he scored his first great legal success by prosecuting Gaius Verres, the corrupt governor of Sicily. This made his name, marking him out as a rising man. He was by now a member of the Senate, and over the following years, he held various offices, culminating in his election as Consul for the year 63 BCE. The consulship – there were two of them elected annually to preside over the deliberations of the Senate and execute its decisions – was Cicero’s platform to oppose the growing challenges to the Roman constitution posed by those who wished to wrest power from the ancient noble families in favour of the equestrian class from which Cicero himself had come. He might not have been a patrician, but he was a conservative constitutionalist, determined to preserve Rome’s ancient but creaky system of Republican government.

Lucius Sergius Catilina, by contrast, was a patrician through and through; the Sergian family claimed that its roots went right back to the very origins of Rome, though his own parents were relatively impoverished. Nevertheless, the young Catilina was determined to follow the cursus honorum, the typical career path of a Roman noble, right to the very top. At eighteen, he served in the army, made a lucrative marriage in his twenties, and when civil war broke out he joined the supporters of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who eventually seized power as dictator.

This seems to be where Catilina started to acquire an unsavoury reputation. Sulla, once in power, engaged in a widespread program of proscriptions, stripping his enemies of their wealth and, in many cases, killing them or sending them into exile. Naturally, that created opportunities for those around him to profit. Catilina made himself rich by arranging for his brother and two brothers-in-law to be proscribed and killed so that he could acquire their estates for a fraction of their true worth. Further rumours of cruelty and avarice followed. He seems to have committed adultery with a Vestal Virgin (an act that, had he been convicted, would have resulted in his death), and after a stint as governor of Africa in 67-66 BCE, allegations of corruption followed him back to Rome, for which he was prosecuted and only narrowly acquitted.

None of this stopped him from trying for the consulship in 65 and 64 BCE. He failed to get elected both times despite having the financial backing of Marcus Crassus, reputed to be the richest man in Rome, and another powerful patrician whose career was on the rise, Gaius Julius Caesar. In 63, he tried once more. Though Cicero, as presiding consul for that year, formally approved Catilina’s candidacy, he nevertheless attacked him, accusing him of inciting the Roman mob by advocating the abolition of all public debts. Failing once again, Catilina seems to have run out of money, and his career might well have ended there.

But he had other plans. In October 63 BCE, Cicero received a delegation of senators at his house who showed him anonymous letters that said Catilina was planning a massacre of the city’s leading politicians, and warning them to leave as soon as possible. Far from fleeing, Cicero instead convened the Senate and read the letter aloud. When, a few days later, news came that an army had been raised in rebellion, led by a centurion named Manlius, a thoroughly alarmed Senate authorised the consuls (Cicero and his colleague Gaius Antonius Hybrida) to take all necessary action to preserve the state.

In early November, Catilina’s conspiracy reached its decisive stage. Still in Rome, and feeling himself safe since the letters that had accused him were anonymous and could, therefore, be shrugged off, he convened a meeting of his co-conspirators and planned to take charge of the nascent rebellion led by Manlius, set fires in various parts of the city to create chaos, murder Cicero (Hybrida was by now out of the city leading an army against Manlius), and then proclaim himself consul.

But Cicero was not at home when his would-be murderers arrived, and he convened the Senate later that day to launch a blistering attack on Catilina, denouncing him and his followers as debauched rogues and dissolute debtors. This speech – the first of four so-called ‘Catilinarian Orations’ – is a masterpiece of rhetoric, cleverly mixing cold logic with damning invective to condemn Catilina and his followers.

Protesting his innocence, the disgraced Catilina fled the city to join Manlius and his rebels in Etruria (modern Tuscany). There, he proclaimed himself consul in obvious defiance of the law. The Senate declared him and Manlius outlaws and dispatched an army to subdue the rebellion. His senatorial co-conspirators were arrested and executed without trial on 5th December, following a fierce debate much influenced by another of Cicero’s speeches. After a short campaign, Catilina’s army was defeated near modern Pistoia, Catilina himself dying on the battlefield.

Catilina may have died in disgrace, but Cicero’s political reputation was made. Much lauded for his suppression of the conspiracy, the Senate voted him the honorific ‘Pater Patriae’ (Father of the Country), and for a while he basked in the popularity bestowed on him by a grateful people. But the conspiracy had been just one of the way stations on the Roman Republic’s long journey to its eventual dissolution, a journey that was to gain new momentum a few years later at the hands of much more skilled and lethal politicians – Gnaius Pompey and Julius Caesar. Cicero opposed them, but to no avail and in 43 BCE, twenty years after his great triumph, he died at the hands of Mark Antony’s thugs.

So, with that background, let us return to the picture. It is, in fact, a large fresco painted by Cesare Maccari in 1888 to decorate a wall of the main reception hall of the Palazzo Madama in Rome, the seat of the modern Italian Senate. Cicero is delivering the first Catilinarian, the only one of the four speeches for which Catilina himself was present.

While Maccari accurately depicts the moment at which the senators, upon hearing Cicero’s allegations, drew away from their erstwhile colleague, leaving him isolated and alone, other aspects of the picture are not historically correct. The Senate was not meeting in the Senate House that day, having been convened at the Temple of Jupiter Stator, not far away at the foot of the Capitoline Hill. Even if they had been meeting at their usual place of assembly, it would not have looked the way that Maccari paints it – the Senate House was a rectangular building, and the senators sat in rows along the walls. And he paints Cicero as a grey beard, when in fact he was only forty-three, two years younger than Catilina.

Still, even with these minor quibbles, the painting has become the iconic representation of the Roman Senate and has been reproduced many times in history books like the one in which I first saw it. The painting may not be accurate, but it is still powerful and highly evocative of an event of great drama and pathos in the history of the Roman Republic. Perhaps it can also serve as a reminder that it often takes the courage of one good man or woman to avert disaster and serve as an inspiration for those whose hearts beat more faintly.

Footnote: Cicero’s life, and the Catilinarian conspiracy, have been treated in historical fiction by Taylor Caldwell, who lionises Cicero in A Pillar of Iron, and Robert Harris, who wrote a trilogy of books – Imperium, Conspirata, and Dictator – that achieves a more balanced portrayal of the great orator. He also appears as a significant character in Colleen McCullough’s Masters of Rome series, though she paints him in a much less flattering light.