It is July 13th, 1793, just one day short of four years since the Parisian masses stormed the Bastille. These have been turbulent few years, and the revolution’s ideals have been severely tested. France is at war with much of Europe, which was shocked by Louis XVI’s execution in January. But the war has gone badly, with General Dumouriez’s defeat and defection in February sparking widespread uprisings across the country, and the revolution itself seemed to be on the verge of collapse.

The ancient monarchy having been swept away, the country is now governed by a National Convention of 749 elected Deputies. Though they are all revolutionaries, they are split between moderate Girondins who fear that the revolution is spiralling out of control, and the more radical Montagnards, led by Maximilien Robespierre and Georges Danton.

The other Montagnard leader is Jean-Paul Marat, a physician, scientist, journalist and one of the most radical voices of the revolution. As the editor of L’Ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People), he has advocated for the execution of all perceived enemies of the revolution. His rhetoric is passionate, his demands for justice relentless, and his paranoia about counter-revolutionaries extreme. Like his colleagues, he favours the most vigorous action to preserve the gains made since 1789.

Just a month ago, Marat played a crucial part in the insurrection of 2nd June, inciting the people to rise up and force the Convention to denounce the governing Girondins and then leading their prosecution on the floor of the Convention itself; the arrest of 29 Girondins was the end of the moderate faction’s power to direct the revolution, and a great triumph for Marat.

But Marat is a sick man. He suffers from a chronic skin condition, possibly dermatitis or a related ailment, which confines him to medicinal baths for long periods, a vinegar-soaked turban around his head to ease the itching of his scalp. No longer able to attend meetings of the National Convention, he has retired but continues his political work from his bath, writing articles and issuing decrees from this unlikely setting.

He is unaware that not far away, at the Hotel Providence, a young woman named Charlotte Corday is preparing to kill him. From a noble but impoverished Norman family, she has become disillusioned as she watches the revolutionary violence spin out of control. She opposed the murder of King Louis and now fears that the radicals will drive the country to civil war. Resolving to do something about it, she has travelled to Paris from her home in Caen a few days ago with the intention of assassinating the dangerous revolutionary Marat, whom she sees as the principal instigator of the bloodshed. His death will, she believes, restore stability to France.

Her initial plan was to make a dramatic example of him by killing him on the floor of the National Convention. But when she arrives in Paris, she discovers that Marat no longer attends sessions of the convention, so she must come up with another plan. Making her way to Marat’s residence, she convinces Catherine Evrard, the sister of Marat’s fiancé, to let her in, claiming she has information about a Girondin plot in her home city of Caen. Marat, ever eager for intelligence on counter-revolutionary activities, allows her into his chamber, where he is sitting in his bath as usual, working on some tract or another.

As he begins taking notes from her supposed revelations, Corday suddenly draws the knife she had purchased when she arrived in Paris and plunges it into his chest, piercing his lung and heart. Marat dies almost instantly, reportedly crying out “Aidez-moi, ma chère amie!” (“Help me, my dear friend!”) before collapsing. His cry is loud enough to summon Evrard from the next room, along with the publisher of Marat’s newspaper, who immediately restrain the young woman and summon republican officials who question Corday and arrest her. By now a mob has gathered, and they avoid a lynching with great difficulty.

Corday is subsequently tried and executed by guillotine just a few days later, on July 17th 1793.

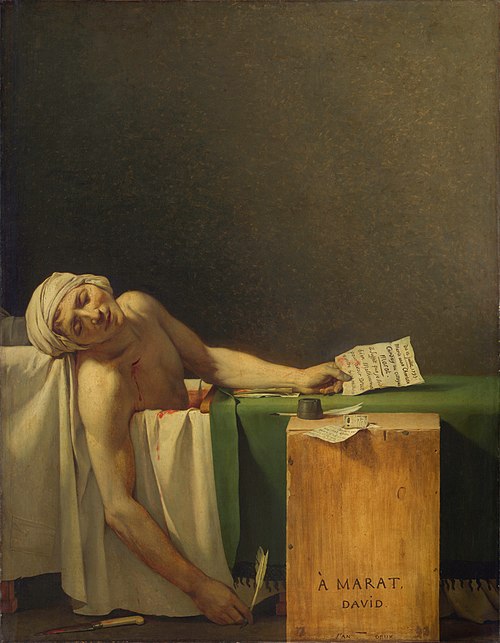

The Death of Marat: David’s Revolutionary Tribute

Far from destabilising the Montagnards, Marat’s death only fueled their cause. The purges of the Reign of Terror intensified, Marat was hailed as a martyr of the Revolution, and his memory was enshrined in the revolutionary legend.

Jacques-Louis David, the leading artist of the Revolution and a personal friend of Marat, was commissioned to create a painting commemorating his fallen comrade. The Death of Marat is a striking and highly idealized depiction of the scene. Marat’s body is portrayed with classical serenity, draped like a Renaissance martyr, his face peaceful despite the brutal nature of his death. His right hand still clutches his pen, symbolizing his dedication to the revolutionary cause. The stark contrast between the luminous figure of Marat and the dark, bare surroundings heightens the dramatic effect.

David’s painting became an iconic image of revolutionary propaganda. It transformed Marat from a controversial firebrand into a saint-like figure of sacrifice. The simplicity and poignancy of the composition evoke comparisons to religious imagery, particularly Michelangelo’s Pietà. However, the reality of Marat’s life and politics was far more complex, and his legacy remains deeply contested.

The death of Marat encapsulates the contradictions of the French Revolution—ideals of liberty clashing with cycles of violence, heroes becoming villains, and vice versa. Charlotte Corday saw herself as a liberator; the Jacobins turned Marat into a martyr. David’s painting ensured that this moment would be remembered not just as an act of political murder, but as a powerful symbol of revolutionary sacrifice. Over two centuries later, The Death of Marat continues to provoke debate, standing as a testament to both the power of art and the enduring complexities of history.