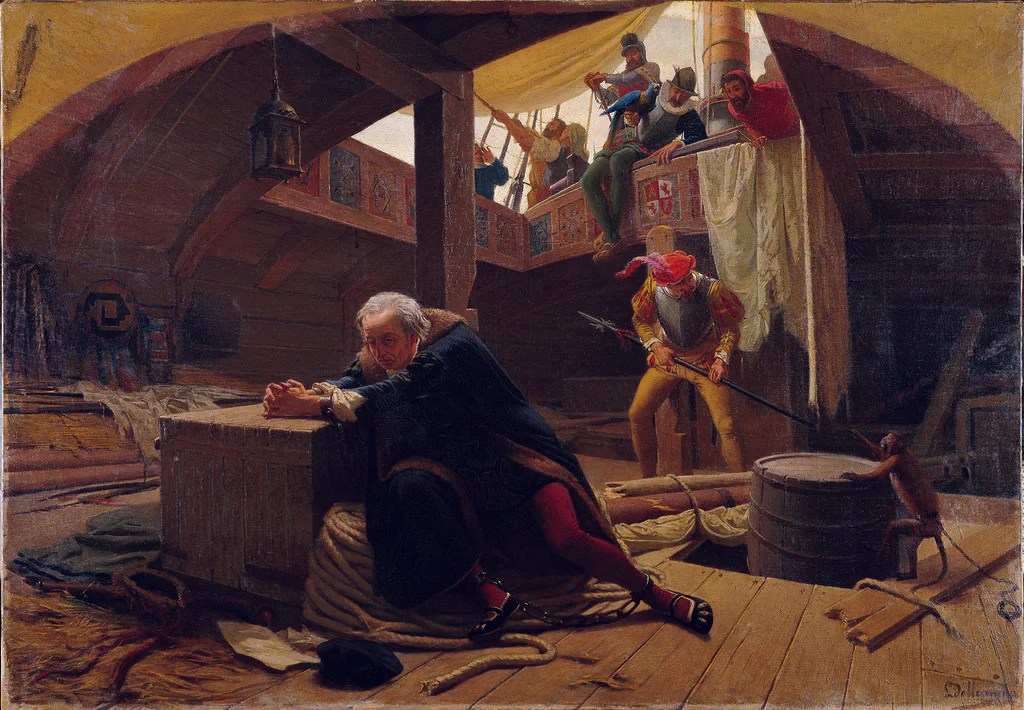

It’s not the image of Christopher Columbus that we’re used to. Not the proud, stiff-backed admiral on the deck of the Santa María, or the discoverer planting flags in virgin sand. In Lorenzo Delleani’s Christopher Columbus in Chains, we find instead a man broken, slumped in a desolate landscape of stone and shadow. There are no ships on the horizon, no cheering crowds. Just shackles on his wrists, and the indignity of betrayal. When I visited the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Genoa—a city proud of its son—this painting made an indelible impression on me.

Delleani, better known for his impressionistic landscapes of Piedmont and the Alps, here turns to a historical subject with a raw theatricality. It’s almost cinematic: the drama isn’t in the action but in the aftermath. And it’s an aftermath worth revisiting.

The Return in Chains

The scene portrayed is Columbus’s ignominious return to Spain in 1500. In the six years between his first voyage in 1492 and his third voyage in 1498, the colony he had established on the island of Hispaniola had become the centre of Spanish expansion in the New World. As Governor of the Indies, it was also his capital and the source of considerable wealth for himself and his brothers. But when Columbus arrived there in August of 1498 after exploring the southern end of the Caribbean chain, he found the colony in chaos.

The cause of the trouble was his harsh rule, a regime of paranoia and brutality, which had sparked rebellion among the Spanish settlers. Accusations of tyranny, corruption, and even heresy were dispatched back to the court in Spain. The Catholic Monarchs—Ferdinand and Isabella—could not afford further scandal, and in response, they sent Francisco de Bobadilla, a knight of Calatrava, not merely as a royal inspector but with sweeping powers to investigate—and to remove. Bobadilla wasted no time. Within weeks of his arrival, he had Columbus arrested, along with his brothers Bartholomew and Diego. They were sent back to Spain in chains.

This is the moment Delleani captures. Columbus, shackled and disgraced, arrives at Cádiz in late 1500, not as a hero but as a prisoner.

The Man and the Myth

To some contemporaries, this was justice. Columbus’s rule over Hispaniola had been marked by arbitrary punishments, the forced labour of native populations, and a near-total breakdown of civil order. Bartolomé de las Casas, later the “Protector of the Indians,” would write damningly of the atrocities committed under Columbus’s regime. To others, however, his arrest was a betrayal. He had opened the gates of empire—surely, they thought, he deserved honour, not humiliation.

Columbus himself saw it this way. With his characteristic sense of theatre, he refused to allow the chains to be removed until he stood before the king and queen in Granada. According to later accounts, he even kept them with him until his death, as a bitter symbol of injustice. “I am not the first admiral to be put in irons,” he wrote, “but I am the first to have done so much for so little reward.”

But the Catholic Monarchs were, it seems, persuaded. Having allowed him to languish in jail for six weeks, they summoned him to the Alhambra Palace in Granada, where they expressed their shock and displeasure at Bobadilla’s actions. Columbus and his brothers were released, and their wealth was restored. The monarchs even agreed, after a suitable amount of haggling (something Ferdinand could never resist), to fund a fourth voyage of exploration.

Delleani’s Interpretation

Painted around 1863, Delleani’s version is tinged with the romanticism of the 19th century’s rediscovery of Columbus as a civilising hero. Italy, newly unified and eager for national symbols, eagerly adopted Columbus as a kind of proto-Italian champion. The fact that he died poor and largely forgotten gave his story a tragic nobility. Delleani’s Columbus isn’t a tyrant or a conquistador—he’s a scapegoat, a man undone by the very forces he served.

That this painting hangs in Genoa’s Galleria d’Arte Moderna carries a quiet irony. Genoa claims Columbus as a native son, yet his legacy has always been contested. In Spain, he was the outsider who overreached. In the Americas, his name variously evokes conquest, colonisation, and erasure. But in this gallery, in this moment, he is simply a man broken by the very empire he helped create; he is alone, shackled, and disillusioned, no longer the master of ships or the agent of destiny.

Lorenzo Delleani’s “Christopher Columbus in Chains” is on permanent display at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Genoa. If you’re in the city, it is well worth a visit—not only for Delleani’s painting but for the very fine collection of Italian modernist pictures.