If you lived in Renaissance Europe and took a fancy to make a list of the rulers of the various states, almost all of them would have been male. The obvious exception would have been Queen Elizabeth I of England, who was, in the eyes of Catholic Europe at least, double-damned for being both a Protestant and, even more of an abomination, a woman ruler.

But Elizabeth was not the only female to rule from a throne or exercise their power directly in courts, councils, and even on the battlefield. Some ruled openly, others from behind the scenes, but all of them left a lasting legacy. Here are ten women who proved that Renaissance power was not just a man’s game.

Louise of Savoy (1476–1531)

Mother, Regent, Diplomat

Louise of Savoy was more than the mother of King Francis I of France—she was a consummate political operator. Twice appointed Regent during her son’s absence, she oversaw France’s internal stability while he was at war or held prisoner. Her skill in governance during Francis’s captivity in Spain after the Battle of Pavia was especially critical, as she managed negotiations for his release and maintained her son’s fragile throne.

She also helped negotiate the Ladies’ Peace of Cambrai in 1529 with her counterpart Margaret of Austria, ending a costly war with the Holy Roman Empire. That two women orchestrated such a treaty amid male-dominated diplomacy stunned Europe—and highlighted their quiet dominance behind the curtain of power.

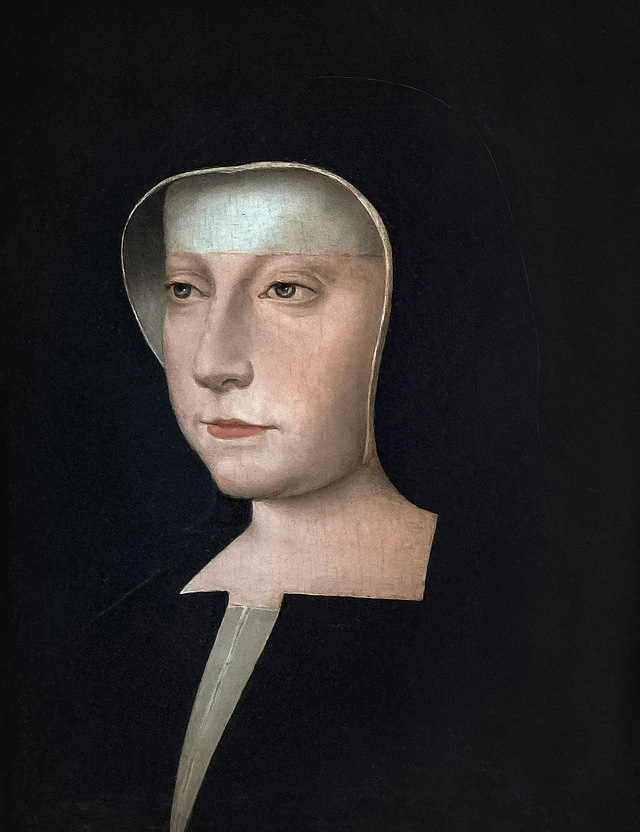

Margaret of Austria (1480–1530)

Governor of the Netherlands, Architect of Peace

Margaret of Austria served as regent of the Habsburg Netherlands and ruled with a steady hand for over twenty years. As aunt to Emperor Charles V, she managed the affairs of a sprawling and restive territory with legal reforms, careful diplomacy, and a sense of cultural refinement. Her court at Mechelen became a centre of learning, letters, and humanist thought.

Her most enduring legacy is the Ladies’ Peace of Cambrai, which she negotiated with Louise of Savoy. It demonstrated not only her diplomatic intelligence but her vision for European stability. While men made war, Margaret made peace—and ensured that the Netherlands remained one of the most prosperous corners of Europe.

Queen Christina of Denmark (1521–1590)

Royal Widow, Political Survivor

Christina of Denmark was widowed young and famously declined Henry VIII’s hand in marriage, quipping that she would only marry him “if I had two heads.” This shrewd political statement won her admiration across Europe and allowed her to retain her independence. She returned to the Habsburg court and later married the Duke of Lorraine, taking on a leading role there.

As Duchess of Lorraine, she governed effectively during her son’s minority and preserved the duchy’s autonomy. Her political acumen allowed her to balance French and Imperial interests, maintaining stability in a time of increasing religious tension.

Margaret Tudor (1489–1541)

Queen of Scots, Mother of a Dynasty

Margaret Tudor, elder sister of Henry VIII, became Queen of Scotland through her marriage to James IV. After his death at Flodden, she served as regent for her infant son James V during his minority, attempting to control a fractious nobility while safeguarding the Stuart throne. Though her regency was challenged, she remained a significant force in Scottish politics.

Her descendants ultimately united the crowns of England and Scotland. Through her great-grandson James VI, the Tudor and Stuart lines merged, making her one of the most important dynastic figures in British history.

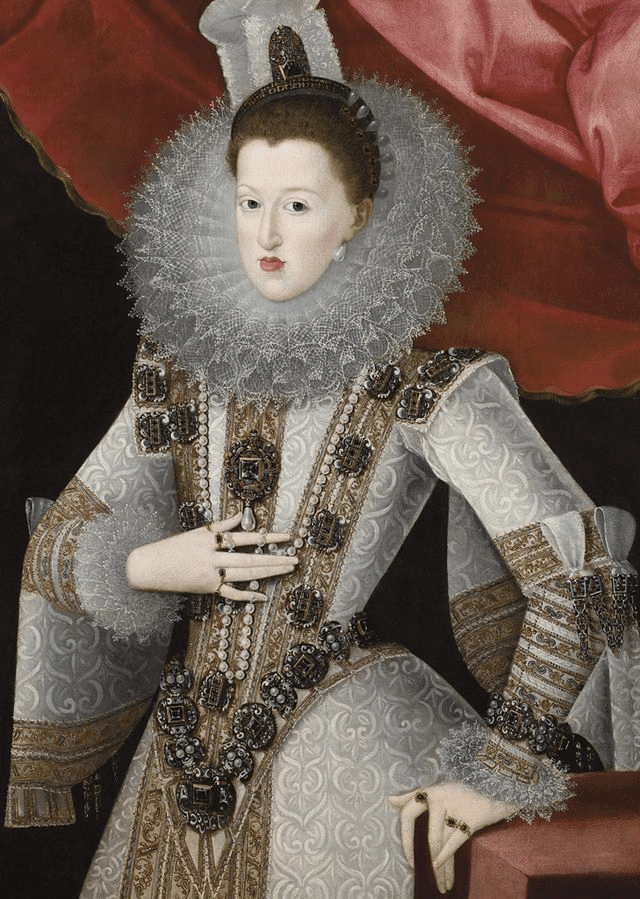

Catherine de’ Medici (1519–1589)

Queen Mother, Political Powerhouse

Catherine de’ Medici was queen, queen mother, and regent of France during the religious civil wars that tore the country apart. She was one of the most influential figures of 16th-century Europe, manipulating alliances, royal marriages, and state policy to protect her sons’ throne and the fragile French monarchy.

Despite her association with the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, she was often a voice for religious moderation. She also promoted the arts, patronised astrologers, and helped shape the courtly culture of the French Renaissance. Her political survival and dominance in a male-dominated court were nothing short of extraordinary.

Marguerite of Navarre (1492–1549)

Scholar, Reformer, Sister of the King

Marguerite of Navarre was a literary and political figure of real significance. As the sister of Francis I and Queen of Navarre, she used her influence to shelter Protestant thinkers and moderate religious tensions in France. She was a key patron of humanist scholars and encouraged a climate of intellectual inquiry.

Her literary work The Heptaméron is considered a foundational text of French literature, offering sharp social commentary from a female point of view. She acted as an intermediary between factions at court and helped pave the way for later religious reform in France.

Nurbanu Sultan (c. 1525–1583)

Venetian Noblewoman Turned Ottoman Regent

Nurbanu Sultan, born Cecilia Venier-Baffo, was captured by the Ottomans and rose to become the wife of Sultan Selim II and mother of Murad III. As Valide Sultan (Queen Mother), she effectively ruled the empire during her son’s early reign, orchestrating policy behind the scenes and managing imperial court politics.

She maintained strong relations with Venice and was instrumental in preserving peace and trade in the eastern Mediterranean. Her charitable endowments and architectural patronage left a lasting mark on Ottoman society, demonstrating how women in the harem could hold real political authority.

Isabella d’Este (1474–1539)

First Lady of the Renaissance

Isabella d’Este was not only one of the great patrons of the Renaissance but also a politically capable regent. While her husband, Francesco Gonzaga, was often away on military campaigns, she governed Mantua and later protected it during times of crisis. Her political intelligence earned her respect across Europe.

Her court became a beacon for artists and philosophers. She commissioned works from Leonardo, Titian, and Mantegna, and her studiolo was one of the wonders of the Italian Renaissance. She proved that female patronage could shape the course of cultural history.

Isabella of Castile (1451–1504)

Queen, Conqueror, Patron of Empire

Isabella of Castile was a powerhouse. Alongside her husband Ferdinand of Aragon, she unified Spain, completed the Reconquista, and reformed the administration of the kingdom. Her reign saw the birth of a modern Spanish state and the emergence of Spain as a global empire.

She sponsored Columbus’s voyage in 1492, opening the door to the colonisation of the Americas. A devout Catholic, she also oversaw the establishment of the Inquisition and the expulsion of Jews from Spain—decisions that had lasting consequences for Spanish history and identity.

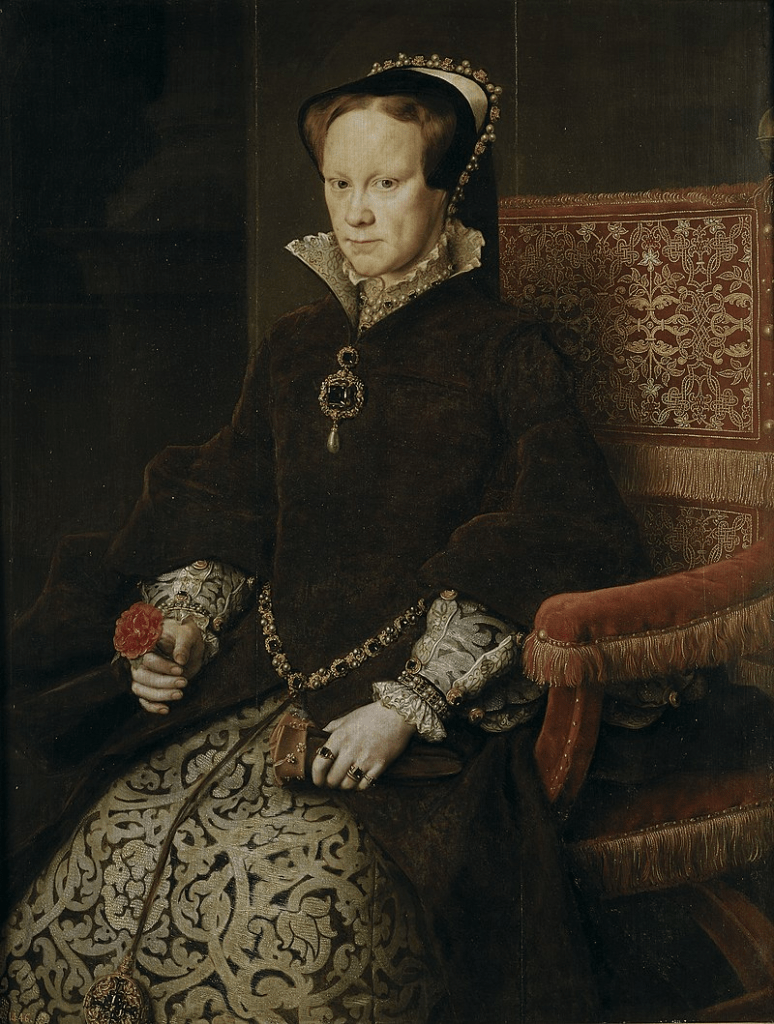

Mary I of England (1516–1558)

England’s First Queen Regnant

Mary I, daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, fought to reclaim her throne and establish her authority as England’s first ruling queen. She deposed Lady Jane Grey and successfully asserted her legitimacy, ruling for five years during one of the most fraught periods in English religious history.

Her re-establishment of Catholicism, however brutal, was an assertive and conscious reversal of Protestant reform. Though her legacy is clouded by the burnings of Protestant martyrs, her reign paved the way for female monarchy and left England better prepared for the long and transformational rule of her sister, Elizabeth I.

These ten women were not anomalies, but part of a broader—if often obscured—history of female power. Whether as regents, rulers, diplomats or patrons, they shaped the Renaissance world not just from behind the scenes, but at its very centre.